If God does not exist, man, therefore, is only beholden to man–and in turn, all is permissible.

The quintessential existentialist claim of “existence prior to essence” traverses in the opposite direction of thousands of years of thought and the commonly held subscription that the Western world has been raised on–“essence prior to existence.” Granted, those making such existentialist claims prior to the Enlightenment were burned at the stake; being branded a heretic silenced many forms of thought–existentialism being the antithesis.

Regardless, the crux of the debate centralizes around the idea of intelligent design and if man is a creation of God; further, and if so, then each of us are imprinted with a sense of meaning, destiny, essence, and / or soul prior to being born. Existentialist reject this position and believe that man is a construct of nature and the creator of his own life. As Sartre puts it, man “appears on the scene, and, only afterwards, defines himself… Not only is man what he conceives himself to be, but he is also only what he wills himself to be after being thrust toward existence” (Sartre, 15). This concept requires that each man becomes aware of what he truly is and that he takes responsibility for his existence (Sartre, 16).

Responsibility is a central theme and paralyzing concept once existentialism is fully understood. Without being beholden to God or notions of good and evil, one’s actions rest solely ones shoulders. Commonly, this is expressed as anguish—the deep feeling of being accountable for the life one chooses, along with the societal structures we all create. A choice for oneself is a choice for mankind, and each man is directly responsible to the other men for whom his choices involve (Sartre, 21). Acknowledging the burden of such choices creates a deep and solemn respect for making the proper choice; something of which is not always apparent.

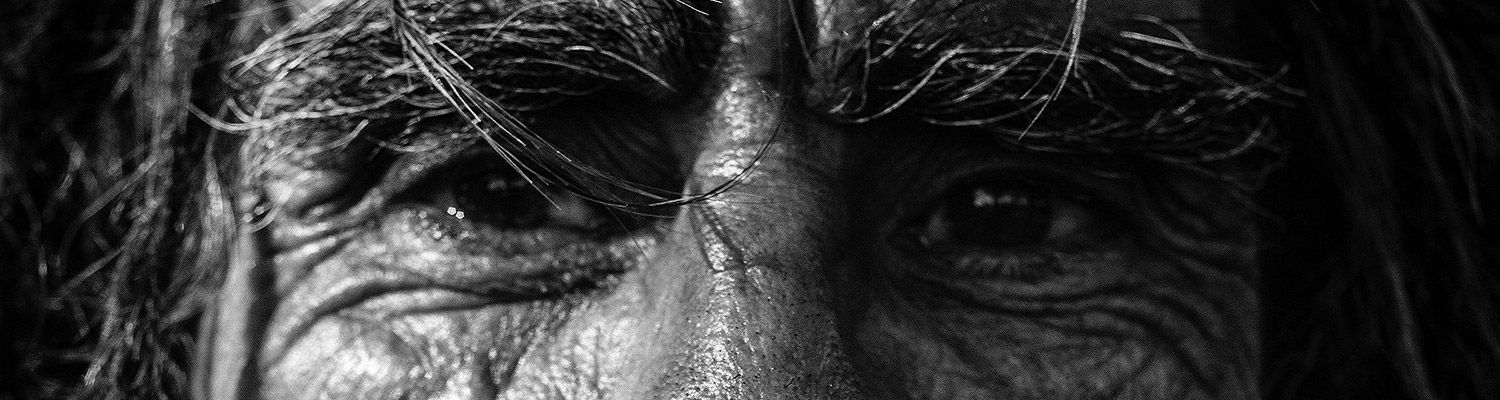

Under the traditional model of essence prior to existence, man could to turn to God when struggling with difficult decisions. Without the existence of God, there is no one to offer man guidance, which leads to a pitiful feeling of abandonment and loneliness. Moreover, if God does not exist, man therefore is only beholden to man, and in turn all is permissible (Sartre, 22). With no prescribed structure of right and wrong, moral and immoral, man has no innate nature to cling to—he is forlorn—alone and with no excuses. (Sartre, 23).

Forced to accept the entirety of his actions, man is bound to despair as the consequences of his actions do not always align with his intention. One can only choose his actions based on probabilities of various outcomes; however, self-evidently, probabilities are not certainties and one is forced to make choices without ever fully knowing the outcome of his actions (Sartre, 29). Despair arises out of the results of choice–the complete and total accountability for the consequences of his choices and actions regardless of the outcome.

Sartre continues by establishing a foundation of truth, harkening back to Descartes’ "I think, therefore, I am". Sartre finds this to be the prime example of consciousness, however he inverts the theory by saying, “every theory which takes man out of the moment in which he becomes aware of himself is a theory which confounds truth” (Sartre, 36). For any theory of human life beyond Descartes’ Cartesian cogito–I am conscious, therefore I exist–is merely a possibility, and doctrines not bound to this primary truth “dissolve into thin air” (Sartre, 36).

Moreover, Sartre asserts that this cogito assumption of existence is the only theory that gives man dignity and doesn’t reduce him to an object (Sartre, 37). Man doesn’t come to the conclusion of "I think" in a vacuum, therefore as we find ourselves, we find others as well—all of humanity being a condition of our own existence (Sartre, 37). A single man fails to be anything without others to recognize him as something.

Works Cited

Sartre, John-Paul. Existentialism and Human Emotions. 1957.