The Future of AI: A Philosopher's Call To Arms

I’m calling for every philosopher of every disciple to wipe their desks and earnestly devote to artificial intelligence.

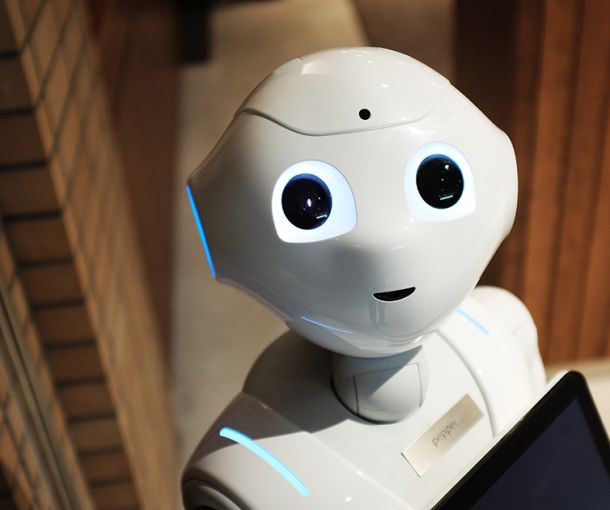

With the likes of Siri, Alexa, and Google jibber jabbering a response to our commands, and the inspiration of science fiction bringing to life replicants, droids, Johnny 5, Wally, Terminators, Hal, and Bender; witnessing these seemingly human heaps of metal naturally leads to the contemplation of what if they were real? Given our personal and institutional dependence on technology; you, me, and Joey Baggadonuts–along with Elon Musk, Stephen Hawking, Nick Bostrom and Daniel Dennett–feel compelled to image what a machine with human-like tendencies might be like.

In theory, universally everyone seems to agree that human-like machines are a possibility—after that, everything is on the table from civilization becoming a god-like utopia, to the annihilation of mankind, to AI being an overly complex benign tool. Each of these wild, colorful, and downright insightful predictions begin at the cusp of the technological horizon, or otherwise known as the singularity.

I — The AI Singularity

The technological singularity marks the point beyond prediction. The theory holds that machines will become so advanced that they will gain an intelligence of their own. This intelligence will duplicate (independent of humans) and compound to the point of super-intelligence, or an intelligence greater than that of a human being. Should technology reach this state of being, the vast possibilities of outcomes are so great and dramatically different from one another that no quantifiable predictions can be made as to how the event will impact the world or human beings themselves.

Given the unpredictable nature of such a monumental event, concern over worst-case-scenarios is a typical and natural response. The unknown has always lead to thoughts of fear, but being unable to dismiss the possibilities only enflames them. The thing that separates humans from all other species on the planet is our superior intelligence—we are the nerds of the animal kingdom because we are certainly not the biggest, strongest, fastest, or even the coolest. This intelligence allows us to dominate other species, control portions of our environment, and aid and advance our survival.

The fear is, should another entity come along that surpasses us as the leading intelligence on the planet—our destiny, effectively, would then fall into their hands. Pragmatically speaking, there are two conditions that would ensure humanity’s survival. One, we possess no existential threat to the new technological super-intelligence. They’re so beyond us, or different from us—possibly only existing in design space—that they don’t need to worry about us. Two, we provide some sort of use or function for them. They need us for something—perhaps symbiotically. Failure to meet one of these two conditions would create competition for resources and dominance. If an equilibrium within a new ecosystem cannot be established, one side may decided to push the other out—odds favoring the side with superior intelligence.

II — Bostrom and All The Ways You Could Die

In Nick Bostrom’s book Superintelligence he posits that the singularity has already occurred and that we are living the midst of it. I tend to be swayed by his argument. While all of the currently known machines and software programs are firmly within our control, these machines are drastically changing the way we live our daily lives, the jobs we have, our ability to access information—and most importantly—how we solve problems and create new designs.

Right now, machines and humans are living together symbiotically and at this point it’s a complete delusion to think that we could flip the switch and live without them without toppling civilization. While we currently have the physical power and free will to do as we wish, turning off machines would kill hundreds of millions of people and disrupt the semblance of life as we know it. Transport, food, water, medicine—and the list is much longer—all of the basic necessities that sustain modern existence are reliant upon soft-AI machines. Machines are now evolving alongside humans, much the same way language has. I encourage you to try to think without language—the same way I encourage you to try to be a part of society without being the beneficiary of a machine. All but impossible—and each are evolving, surviving, and persisting alongside us.

Bostrom seems to be reacting to the epiphany of this machine dependance similarly as a first time father contemplates an impending birth. The father, pacing back and forth with his hands running through his hair, dismantles every hypothetical scenario of the unborn child from it possibly becoming the next Charlie Manson, to how he may say the wrong thing that scars the child for life at its 9th birthday party, to the heart-wrenching pain and panic of the child being born with a terrible birth defect.

Each machine equivalent of these scenarios are possible, all of them are unknowable, and whatever is to happen in the future is unavoidable. With that said, worrying is like a rocking chair—it may give Bostrom something to do, but it doesn’t get him anywhere. He does a great job of giving context to technology and laying out the current landscape of AI but, ironically, should super-intelligence actually occur as he sees it, he provided the machines with our playbook for curtailing them by making the book available digitally! Some snicker at this criticism saying, “well, if he didn’t do it, someone else would have and it eventually would have wound up online anyway,” which is precisely my point. AI is inevitable and we better move past the insecurities of an expecting father.

As we move deeper beyond the point of prediction, each day that passes we lose the opportunity to constructively shape AI into the being we want it to become—instead worrying about what it could be.

III — Dennett and Darwin Sittin’ In A Tree

Daniel Dennett’s From Bacteria to Bach and Back is a mind blowing opus on the nature of becoming human. Of the 400+ pages, maybe about 15 of them are dedicated to AI and super-intelligence, but of those 15 you aren’t cheated. While Dennett is obviously playing to his strengths and culminating his life’s work on evolution, he also uses this as an opportunity to contrast the very distinct difference between humans and machines, and each of our paths of evolution that potentially dictates our unique abilities for intelligence.

The crux Dennett’s argument is that machines don’t have skin the game—literally. Machines do not possess millions of years of evolutionary history and are not beings made up of neurons and cells struggling for survival—it is this collective struggle that yields consciousness, an advanced evolutionary technique created by arduous bottom-up trial and error giving the being a user-illusion (a consciousness and perspective) to enhance its chances of survival.

Machines, on the other hand, are dependent and parasitic on humans. As currently designed, machines depend upon humans for their survival—not only to provide them with power to operate—but also they require our intelligence to provide them with all of the relevant information about the world that they use to quantify over. Neurons and cells accomplish all of this collectively in a single self-sustaining being, and this struggle alone is what affords brained beings consciousness. To replicate consciousness would be to replicate evolution and its masterful exploitation of survival techniques.

Dennett isn’t saying that human-like machines aren’t possible, but he’s certainly saying that they couldn’t exist as they’re currently designed. However, Dennett doesn’t want to underestimate the brilliant computing power that machines currently possess and our reliance upon them. His greater concern isn’t that of machines forcibly taking over like Bostrom is predicting, but humans ridding themselves of competence by relinquishing their intelligent capabilities to the process of artificial designers.

Machines continue automating evermore complex tasks and humans are having difficulty understanding how machines arrived at their conclusions. “Doing the math” per-say to fact-check a computer is insurmountable given the amount of complex calculation and deep data trolling computers are capable of doing. Dennett is concerned that we will just blindly accept whatever information machines give us, effectively removing us from the research and design process.

Currently we still have to curate the work done by machines, however, as Dennett puts it, “If and when [AI] ever reaches the level of sophistication where it can enter fully into the human practice of reason-giving and reason-evaluating, it will cease to be merely a tool and become a colleague.” Dennett sees human space in this arena shrinking, and the time of machines reaching the ability to explain what for? and how come? questions narrowing. Once they do, humans will transition beyond the tens-of-millennia of our arduous intelligent design—that has afforded us all that we enjoy—into an era of post-intelligent design where machines do all of the R&D creating for us.

Dennett’s greatest concern of machines becoming our creators is if the machine makes a mistake. Our dependence will relinquish human competence and comprehension in acknowledging, correcting, and preventing mistakes from happening.

IV — Philosophers Are Dropping The Ball

Of all the philosophical topics commonly discussed, artificial intelligence is the greatest innovation of humankind and we are in the midst of it; sitting on the brink of it! We are alive during one of the greatest transitions the human species has ever encountered—and the seriousness of this statement is not rhetoric or hyperbole.

AI is a relevant and tangible issue, with massive implications, that seems especially suited for philosopher’s to solve. This is our wheelhouse—language, logic, mind, existentialism, and ethics all coming together; yet philosopher’s are somehow not driving the AI ship.

Perhaps it’s due to thousands of years of passive reflection; we’ve conditioned ourselves to sit back and comment on humanity rather than actively participate in it. However, AI is the philosopher’s Super Bowl—humanity tangibly needs the toil of our predecessors, and we finally have the opportunity to put what we’ve learned and persevered into productive and contributive use—not theoretical ponderings—that steers AI in the direction that we want this innovation to go. It’s going to happen with or without us—but let it be known that we had the opportunity.

I’m calling for every philosopher of every disciple to wipe their desks and earnestly devote to artificial intelligence. Give the designers, engineers, entrepreneurs, lawyers, and politicians the foundation they need so that we can all begin to shape this innovation and be proud of what it is to become.

Works Cited:

Bostrom, Nick. Superintelligence. Oxford. 2014.

Dennett, Daniel. From Bacteria to Bach and Back. Norton. 2017.