The Soul and Ortega: Perspective as Art

The only limitation made upon your future is the choices of your past.

In Ortega’s A Few Drops of Phenomenology, he approaches reality as one approaches a painting in an art gallery. Scenes of life play out on the canvas and depending on where one is standing—the image reveals entirely different meanings, considerations, and understandings. Reality becomes nothing but perspective, and the vibrance of life only increases as one approaches it.

To fully appreciate art, one must immerse themselves in it–and the same holds true for Ortega’s perspectivism of life and reality. Emotional distance is the only thing that separates lived reality from observed reality, and all perspectives are intimately depended upon one’s experience and participation with lived reality.

It is this understanding of lived reality that gives observed reality any meaning or relevance; otherwise all observed reality would fill one’s ears as a foreign language. Perhaps beautiful in it’s colors and timbre, but understanding the language's meaning would be as effective as translating the wind. Ortega explains, “in the scale of realities, lived reality holds a peculiar primacy which compels us to regard it as the reality” (A Few Drops of Phenomenology). Or, what is commonly referred to as "human” reality. All other abstractions of reality are observational, and the notion of objective reality is a human construct.

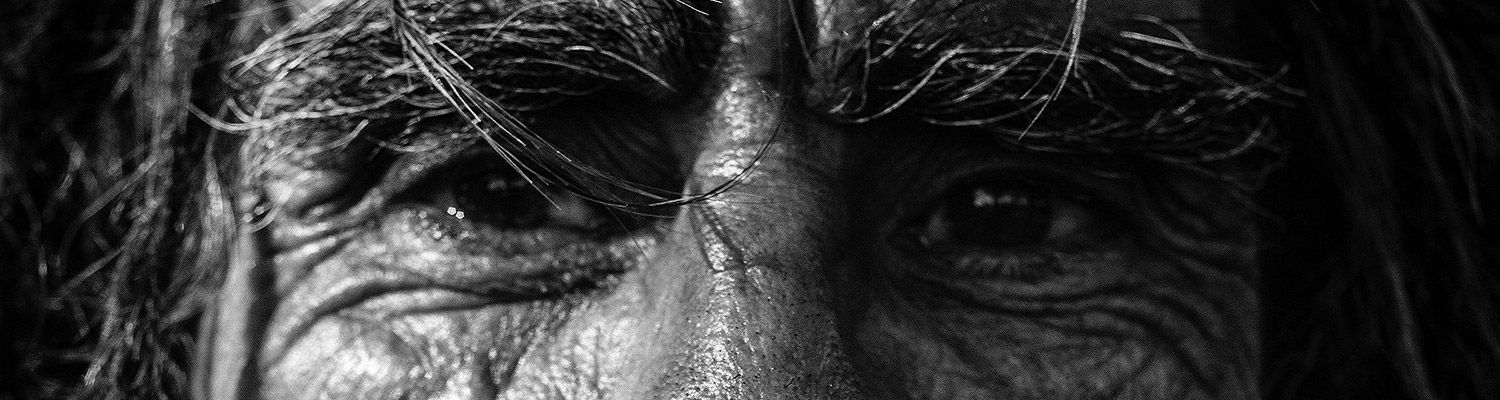

In a separate work, Man Has No Nature, Ortega draws the comparison of man by describing the complexity of our existence as an “ontological centaur”. That is to say that man is not merely half animal, but that we are also half mortal and half mythical, half empirical and half rational, half physical and half metaphysical. Perhaps to be more insightful, Ortega puts it; “[man is] partly akin to nature and partly not, at once natural and extra-natural… half immersed in nature, half transcending it.” A symbiotic coexistence between two contrary and competing forces that yields one’s tangible existence and the meaning ascribed behind it.

Expanding upon the illustration of the centaur, Ortega relates the horse-half of man as unquestioned nature. The horse is simply a corporeal body providing earthly existence, creating no quarrel other than the limitations a body provides. The extra-natural part, the man-half of the horse, is one’s true identity or personality—what we would refer to as “our self”. While this is a form of dualism, Ortega is careful not to conflate it with Cartesian ideology, or as he would call it, “speculative wizardry”. The central distinction between Ortega’s dualism and the Cartesian model is that, at birth, a man has and is nothing; it is only the “project of life” or accumulation of one’s aspirations and desires (the future), combined with his actions (the past), that truly makes him who he is.

The “man-half” of the centaur is unlike all other natural creatures on earth in that it is not defined by what it is, but by “what it is not yet, a being that consists in not-yet-being” (Man Has No Nature). Ortega’s inversion and shift in perception crushes determinism and places man at the center of his own destiny—allowing him the ability to become whatever he chooses. While this prospect is exhilarating, its consequences can seem paralyzing, for “the weightiest thing [man] has to do is to determine what he is going to be” (Man Has No Nature).

As man carries his decisions and experiences with him throughout life, the only limitation made upon his future is the choices of his past. “If we do not know what he is going to be, we know what he is not going to be. Man lives in view of his past. Man, in a word, has no nature; what he has is history” (Man Has No Nature).

Works Cited:

Ortega y Gasset, Jose. "The Dehumanization of Art: A Few Drops of Phenomenology". 1925.

Ortega y Gasset, Jose. "Man Has No Nature". 1961.