The Anglo-Zanzibar War: The Shortest War in History

On every measurable scale, no matter which side you are sympathetic toward, The Shortest War In History adds to the long list of Unjust wars plaguing history.

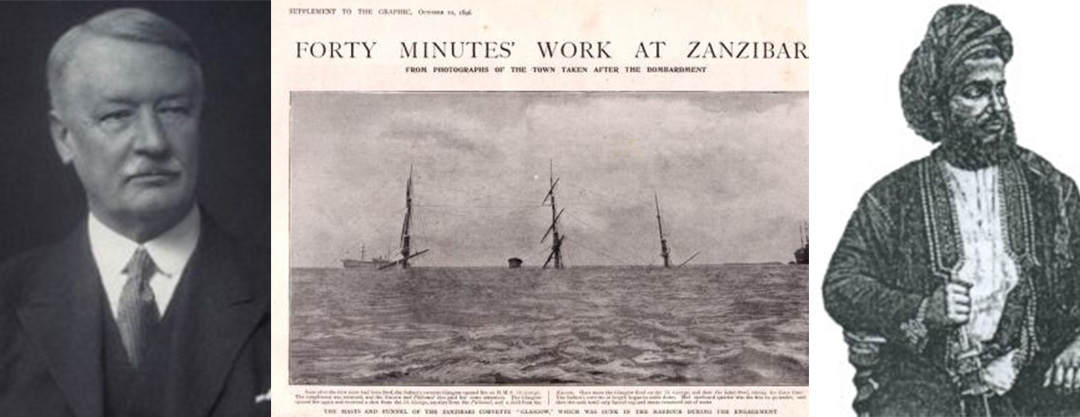

In keeping with my theme of researching the Justness of odd and absurd wars, the Anglo-Zanzibar War makes the list as it is regarded as the shortest war in history. Fierce debates have risen over the actual length of the war; Zanzibar sympathizers insisting that the conflict lasted for at least 45 minutes, while British historians claim it was a mere 38 minutes. Let’s just call it an even 40.

Like most dumb wars, Great Britain was a belligerent and its main cause was ensuring that the sun never sets on the British flag. Zanzibar, on the other hand, simply didn’t believe that Great Britain had the stones to fire on them. They were wrong. With a scene straight out of The Simpsons—Bart playing the role of Zanzibar and Lisa playing the role of Great Britain—ultimatums were levied with the attitude that if Zanzibar didn’t comply, it would be their own fault. What more justification for war could O’Brien need?

Background and Competent Authority

Zanzibar, the tiny city-state island off of the coast of Tanzania, has a rich history of Native, Arab, Portuguese, Spanish, British, French, and German inhabitants. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, East Africa was central in the slave trade and Zanzibar acted as its primary port. Flash to 1890 and within the height of British imperialism, Germany and Great Britain signed a treaty to divvy up the East African territory (Johnson). Half way across the world in some dank, pipe-smoke filled parliamentary office of Her Majesty, Germany secures now-Tanzania and Great Britain obtains Zanzibar and now-Kenya. Unable to govern her immense global colonies on her own, Great Britain appoints “puppet” leaders favorable to her cause to look after specific regions (Johnson). In Zanzibar’s case, Hamad bin Thuwaini was appointed as Sultan in 1893—in direct conflict with the “rightful” heir of Sayid Khalid ibn Barghash who was a young and passionate leader that held the favor of the people, and a man that the British Consul saw as a threat (Knappert). It’s important to note that just because Germany and Great Britain agreed to this treaty, that doesn’t mean than any of the inhabitants of East Africa or Zanzibar did, or officially acknowledged these foreign powers as their rulers. Technically, Great Britain was the legal authority over Zanzibar, but only because Great Britain wrote the laws.

A crucial factor leading to this war was the slave trade. Over the course of decades, Great Britain had been working to abolish slavery and end the trade of slaves within the region. Zanzibar directly opposed this as slavery was their primary economy and had been for centuries (Knappert). Khalid Barghash was a slave owner and represented the desire of the (free) people to continue slavery, and he did not share British view of how the region should be administered.

On August 25, 1896, British appointed Sultan Thuwaini suddenly and mysteriously died, and within hours Khalid Barghash had moved into the palace and took the throne without British approval (Johnson). While there is no official evidence, it has long been suspected that Barghash had Thuwaini poisoned (Thuwaini being Barghash’s uncle, no less) on purpose to seize power (Johnson). Within one day, Barghash had raised a well-equipped army of 3,000 that occupied the Zanzibar palace, along with a moderately armored Royal Yacht that patrolled the harbor—all weapons coming as diplomatic gifts from the British to former Sultan Thuwaini (Johnson). Needless to say, Chief British Consul Basil Cave, didn’t like the recent turn of events and immediately told Barghash to stand down and remove himself from the palace.

As related to O’Brien’s jus ad bellum of competent authority, the situation can be viewed de facto or de jure. There is plenty of evidence to claim that Great Britain obtained their de jure authority over Zanzibar unjustly, and therefore any of their subsequent authority was unjust. The treaty Great Britain agreed to was with Germany, and not with the Sultans or region it occupied. Even though they claimed Zanzibar, de facto Zanzibar can be seen as its own independent state with its Sultans simply choosing to go along with Great Britain over certain policies and not that the state had relinquished their sovereignty to them.

Moreover, British Parliament never voted or officially declared war on Zanzibar—not that they ever really did at the time (they were conducting aggressive military action all over the world, and the conflict with Zanzibar was business as usual). British consul Cave immediately communicated the situation with the Foreign Office in a telegram that asked permission to use force: “Are we authorised in the event of all attempts at a peaceful solution proving useless, to fire on the Palace from the men-of-war?” The reply Cave received was: “You are authorised to adopt whatever measures you may consider necessary, and will be supported in your action by Her Majesty’s Government. Do not, however, attempt to take any action which you are not certain of being able to accomplish successfully” (Johnson). While this is the only authorization that Cave needed to justify his actions, these actions do not justify Great Britain as a whole.

There is no doubt that O’Brien would oppose the legitimacy of Barghash—the killing of his uncle to seize power—however, originally, Barghash should have been Sultan of Zanzibar and would have been the legitimate authority to declare war if it weren’t for Great Britain’s unjust appointment of Thuwaini. Legally, Barghash is not the legitimate authority according to Great Britain, but de facto due to the death of Thuwaini, Barghash would have been the rightful heir to the throne.

Pragmatically, both sides are able to rationalize their actions and claim authority. However, regardless whether the situation is viewed as de facto or de jure, morally neither side is able to claim their authority as Just, as both obtained this authority unjustly.

Just Cause and Right Intention

Examining both sides of this war through O’Brien’s requirements of just cause hinge primarily on sovereignty. According to the British, Zanzibar is part of the British Empire and they have every right to claim it and enforce their method of government upon it. According to Zanzibar, Barghash is the rightful ruler and the foreign imposition of Great Britain is a violation of their sovereignty. Much like when establishing legitimate authority, both sides have reasonable claim of sovereignty; however, the method each side used to acquire sovereignty was unjust, therefore making the rest of their actions that lead to war unjust.

While I don’t believe either side was primarily trying to restore rights to its citizens that were wrongfully denied, sub-arguments of this are brought to attention over slavery. The non-British merchants, political class, and Zanzibar economy depended on slavery and slave trade, and Barghash believed he was restoring the rights of his people to continue this practice. More than several millennia had given precedent to moral acceptability of slavery and Barghash was attempting to seize power to continue this way of life. From our point in history it seems easy, and almost obligatory, to condemn Barghash for his views regarding slavery, but that would be an unfair evaluation given the context of the time. The problem with all moral evaluation is that it is dependent upon perspective, and our own civil war was fought less than 30 years prior over the same issue. While slavery was on its way out across most of the world, this change in a long-standing practice was happening rapidly in the grand scheme of history. Given this, I am unwilling to declare Barghash unjust for his politics, but his concern over the rights of his people were clearly secondary to his primary objective of gaining power. Therefore, any arguments Barghash could make regarding the restorations of rights or re-establishing Just order fail the requirements of a Just war.

Throughout the mid-nineteenth century, Great Britain changed its views of slavery and they believed that by abolishing slavery they were restoring inalienable human rights that had been wrongfully denied to slaves. This had become an encompassing policy of the empire, and not a one-off rule it had created specifically for Zanzibar. However, all documentation regarding this conflict cite Great Britain as merely re-establishing just order. While subduing slavery and proponents of it fit their overall agenda, this conflict ultimately had very little to do with slavery itself. Great Britain unequivocally viewed Barghash as the un-rightful Sultan of Zanzibar and were going to remove him regardless of his political agenda. Again, their authority to do this can be called into question given Great Britain’s morally unjust method of securing power over the region.

Both the British consul and Barghash had known of each other prior to the conflict and had (poor) relations in the past (Frankl). When Barghash seized control of the palace, there were no diplomatic negotiations but only British ultimatums. Great Britain demanded that Barghash remove himself from power; if he did not, they would attack (Johnson). This was the only offer given to Zanzibar, and the next day on August 26th Basil Cave gave Barghash his final ultimatum, ordering him to stand down by 9am the next morning (Wikipedia). Barghash replied; “We have no intention of hauling down our flag and we do not believe you would open fire on us.” Cave’s response was simply, “but unless you do as you are told, we shall certainly do so” (Johnson). Promptly at 9am on August 27th, bombardment of the palace ensured.

Clearly, Barghash believed that there would be a diplomatic means to end the conflict. While, allegedly, he did kill the pervious Sultan, he was not holding hostages or forcibly holding the city under his control—in fact, it was the exact opposite. Many throughout Zanzibar pledged themselves to Barghash and willfully joined ranks within his army, recruiting more than 3,000 guards in 24 hours (Frankl). Because Great Britain was unwilling to negotiate with him prior to the appointment of Thuwaini, I believe Barghash felt he had to demonstrate his power in order to gain a sit down with British diplomats to negotiate his authority, with the overall goal of gaining legal British appointment as Sultan. He saw the British ultimatums as a bluff, and succumbing would show his weakness as a leader. However, if he was mistaken, he would unjustly be placing the entire region in danger as he knew there was zero probability of long-term military success against Great Britain. While the British wouldn’t acknowledge him prior to taking action, there was no scenario where military conflict would have achieved his goals. Because of this, Barghash was un-proportional and unjust in seizing control over the palace and raising an army.

Clearly, the British weren’t bluffing and had zero tolerance for Barghash’s method of diplomacy. Nor did they desire to relinquish any power that would allow a possible uprising to grow under Barghash’s command. Instead of viewing Barghash as a charismatic and unifying leader of the region, the British immediately saw him as a threat that needed to be eliminated.

Pragmatically, Great Britain’s proportional calculation to attack made a lot of sense. It was all but a guaranteed one-hour victory and they had no rational reason to not squash any decent against them. They held all of the power and had no reason to negotiate with someone who they felt didn’t share their similar views. While the British didn’t have the immediate troop numbers that Barghash carried, they greatly out-weighed Zanzibar in terms of technology, equipment, skilled fighters, strategic expertise, resources, and regional power.

However, morally and according to O’Brien’s requirements for Just causes of war, the British response fell drastically short of Just proportionality. With their overwhelming military advantage, the British subjected all involved to the horrors of war straight out of the gate by making no effort to explore other means of removing Barghash. Beyond failing to negotiate directly with Barghash, the British could have implemented sanctions and blockades to push him out of power. Literally any other means other than war could have been explored, but none were—making the attack unjust.

Which, finally, leads to the Right intention of the war and the crux of the entire conflict. It is clear that Barghash’s main intention was securing a throne that he felt was rightfully his. It was purely about his own power and glory; any benefits the people of Zanzibar might have seen would have been secondary. Alternatively, as much as Great Britain claims it was re-establishing Just order, they simply disdained Barghash and refused to see him in power no matter the cost. Neither side were seeking lasting peace (rather domination, power, and control) or extending charity to the other side. Because of this, and with consideration of each side’s weak sub-arguments for Just cause, it is clear that neither ultimately fulfilled any of the requirements of jus ad bellum because from the onset neither possessed the Right intention of going to war.

Jus in Bello

As soon as 9am rolled around on August 27th, Great Britain was surgical and masterful in its attack. By 9:02am, the majority of Barghash’s artillery had been destroyed (Johnson), and in the remaining half hour the gifted Royal Yacht had been sunk and the palace walls had collapsed in on themselves. The Zanzibar flag was lowered by British troops in literally 40 minutes from the first shots being fired, making it the shortest war in history.

For being as brief as it was, the casualties Zanzibar suffered were quite high with over 500 of Barghash’s soldiers killed or wounded (Johnson) at an average rate of 12.5 per minute. This is mainly due to the palace being made of wood, and the structure exploding and igniting under the shelling. One British pretty officer was also accidently injured aboard a ship, Great Britain’s only casualty, though he made a full recovery (Johnson).

Great Britain made a conscious effort to only attack the stronghold of Barghash and while records are sparse, there were no report of non-combatants being harmed. The British Navy also forced all civilian vessels out of the harbor the night before the attack, limiting any property damage or casualties to those not involved (Johnson). Also, following the sinking of Zanzibar’s Royal Yacht, the Navy performed a rescue of Barghash’s surviving sailors (Wikipedia).

Given Great Britain’s superb competency in executing the attack, their military conduct during the war was proportional and Just by only attacking strategic targets and limiting collateral damage. Little can be said about Barghash’s military competency as it never landed a blow and didn’t remain a fighting force long enough to be judged, good or bad. It’s important to note that Barghash fled the palace as soon as British shelling began, abandoning his soldier’s and the cause that he had lead them into. He sought asylum from the German Consulate where he was later smuggled out of the country to German-held Tanzania.

Post War Behavior

The British retained control of the city following the attack to lesson looting and add stability to the region. With Barghash no longer a threat, Great Britain appointed Sultan Hamud to the throne of Zanzibar, who was pro-British but remained on a short leash—the position merely being ceremonial (Knappert). As punishment for the war, Zanzibar was ordered to pay reparations to Great Britain for expenses incurred in the amount of 300,000 rupees.

However, that was not the end for Barghash. Great Britain vigorously sought that he be extradited from Germany, though Germany did not comply citing that their extradition treaty with Great Britain specifically excluded political prisoners (Wikipedia). It wasn’t until 1917, after Germany’s loss in World War I and 21 years after The Shortest War In History, when the British invaded East Africa that Barghash was captured (Frankl). Barghash and several of his children and servants were exiled to the tiny island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, where they remained until 1922 (Frankl). Declaring that Barghash no longer posed a threat to British interests, Winston Churchill approved that Barghash may return to East Africa and live in the city of Mombasa. Barghash died in 1927.

Conclusion

It is well documented that Barghash’s motivation for securing the throne of Zanzibar was of anti-British sentiment (Frankl). His methods of gaining power, whether including murder or not, were unjust as he was primarily motivated by power and glory; impassioning Zanzibar citizenry with foreign imperial resentment to only further his own cause. Barghash’s seizure of the palace and failure to comply with British demands only endangered his city and lead to the death of hundreds, squaring off against an enemy he could never defeat. While the citizens of Zanzibar may have been unsatisfied with British rule, Barghash was unquestionably unjust in all the methods he used ad bellum and in bello.

The actions Great Britain took personally against Barghash, and their relentless pursuit of him decades following the war, clearly demonstrates that they did not exhibit the Right intention when going to war. Great Britain sought retribution and was vindictive of Barghash for his actions that lasted only three days, punishing a man who when captured had zero political influence and who had overall caused little damage to Zanzibar or the British Empire. Failing to negotiate with Barghash, or attempting to remove him from power prior to the use of military force, was a disproportional response to re-establish Just order. The ends of Inflicting death upon hundreds did not justify the means of war; rather these actions were a show of force within the region to curtail any possible thoughts of an uprising. Because of this, Great Britain’s ad bellum proportionality and right intention was unjust, along with their unjust actions following the war in regard to Barghash personally. While their conduct during the attack was Just, overall it was an Unjust war, making the use of military force Unjust.

With that, on every measurable scale and no matter which side you are sympathetic toward, The Shortest War In History also adds to the long list of unjust wars throughout history.

Works Cited

“If You Get Hit It’s Your Own Fault.” YouTube, uploaded by The Simpsons, 24, Jun 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fmxLyHQfpLA.

Johnson, Ben. “The Shortest War in History.” Historic-UK.com. www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/The-Shortest-War-in-History/. Accessed 28, Apr. 2018.

Knappert, Jan. “A Short History Of Zanzibar.” Annales Aequatoria, vol. 13, 1992, pp. 15–37.

Frankl, P. J. L. “The Exile of Sayyid Khalid Bin Barghash Al-Busa'Idi: Born Zanzibar C. 1291 AH/AD 1874 Died Mombasa 1345 AH/AD 1927.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 33, no. 2, 2006, pp. 161–177.

“Anglo-Zanzibar War | 3 Minute History.” YouTube, uploaded by Jabzy, 19, Feb. 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x-KVpjrHT0Y.

“Anglo-Zanzibar War.” Wikipedia. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglo-Zanzibar_War. Accessed 30, Apr. 2018.